Microsoft’s mastermind is often lambasted online and in the media – conspiracy theorists also love to target him. But is anyone else doing more to combat COVID-19?

Bill Gates polarises opinion; some view him as a visionary who started a computer revolution, others as a selfless philanthropist. Then there are those who think he’s the quintessential capitalist-cum-predatory business practitioner who has throttled the software sector. Love him or loathe him, he is without doubt one of the most successful entrepreneurs of the 20th century and beyond. The numbers speak volumes: in just over two decades he turned a two-man operation into a multi-billion-dollar giant, becoming the world’s richest man in the process. His story is less about invention and more about innovation and anticipation; the ultra-intelligent American saw an opportunity to adapt existing technology to a specific mar- ket and refused to give up until his company, Microsoft, completely dominated. Reaching such lofty heights has forever elbowed Bill into the public eye and while he’s lined his pockets, his celebrity status subjects him to criticism and controversy, whether it be deserved or not.

Recently, the ex-Microsoft head has been targeted by conspiracy theorists who claim the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation – which has pledged $100 million to combat COVID-19 – has tested virus vaccines on African and Indian children, causing thousands of deaths. Bill and his wife, who once worked alongside him at the technology company, have remained bullish about the accusations. “At a time like this, when the world is facing an unprecedented health and economic crisis, it’s distressing that there are people spreading misinformation when we should be looking for ways to collaborate and save lives,” the couple said in a statement. “Right now, one of the best things we can do to stop the spread of the virus is to spread the facts.”

Born in 1955 in Seattle, Bill’s upbringing was privileged but unremarkable. Things changed when he met his first computer at school as a teenager and it didn’t take long for him to start taking advantage of the primitive software. “Basic computers arrived when I was 13 and they kind of intimidated the teachers so myself and a few others were viewed as the computer experts,” he says. “The teachers were nice enough to let us do the scheduling for the different classes on these machines so I could decide which girls were in my class – I therefore studied with lots of great girls…I didn’t talk to them much but they were there. Learning computer science really does open up some amazing opportunities.”

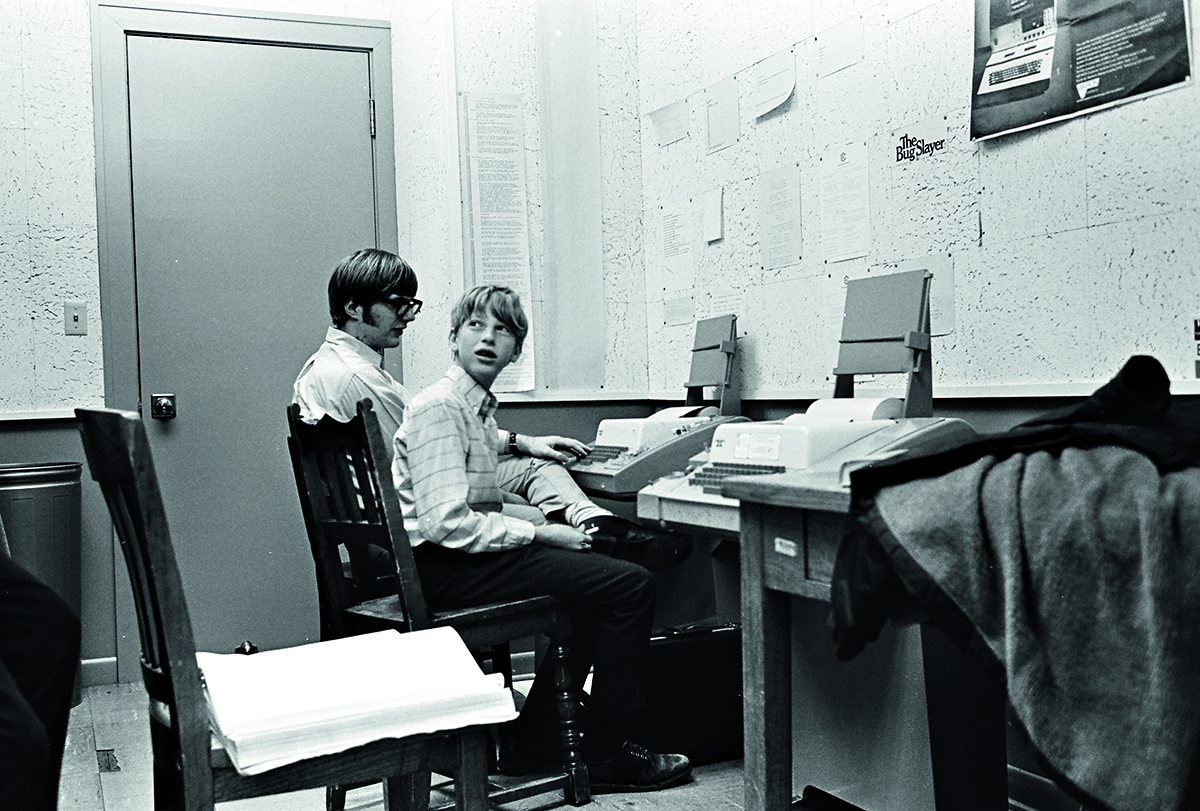

Bill and Paul Allen as teenagers.

At the tender age of 16, Bill and fellow student Paul Allen developed a programme to analyse traffic flow in Seattle called Traf-O-Data, which they sold for $20,000. A tidy sum for a couple of teenagers. They were both accepted into Harvard in 1973 but the duo’s first taste of success in the business world meant they were more interested in money than studying. A year later, Paul chanced upon an article in Popular Electronics magazine about the world’s first microcomputer, the Altair 8800, which appealed to their opportunistic tendencies; they immediately called the manufacturer (MITS in Albuquerque, New Mexico) and told the CEO they had written basic language software for the 8800, despite the fact they didn’t even have access to one. They had no choice but to simulate their programming on another computer and they weren’t even sure their new product would run when they rocked up at MITS HQ. Luckily for them it did, and their lives changed forever. The pair subsequently dropped out of Harvard, moved to New Mexico to work for MITS, and eventually established Microsoft.

A few years later in 1979 they moved Microsoft to their hometown of Seattle where the company skyrocketed. This was largely due to the fact that Bill saw that American multinational technology company IBM was searching for an operating system for its new PC – he quickly snapped up an existing system from a small company for peanuts (relatively speaking) and developed it into MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System) before licensing it to IBM. “The genius of this move,” recalled Paul, “was that Microsoft retained the rights to license MS-DOS to other computer manufacturers.” The wheels of the computer revolution were in motion. In 1983, Paul was forced to resign after being struck down with Hodgkin’s disease. He beat the cancer but rumours still abound about why he departed Microsoft – some claim Bill shoved him out, others say both the illness and other opportunities changed his perspective on life, so he opted to pursue a different path.

Read the full article here.